|

Commentary:

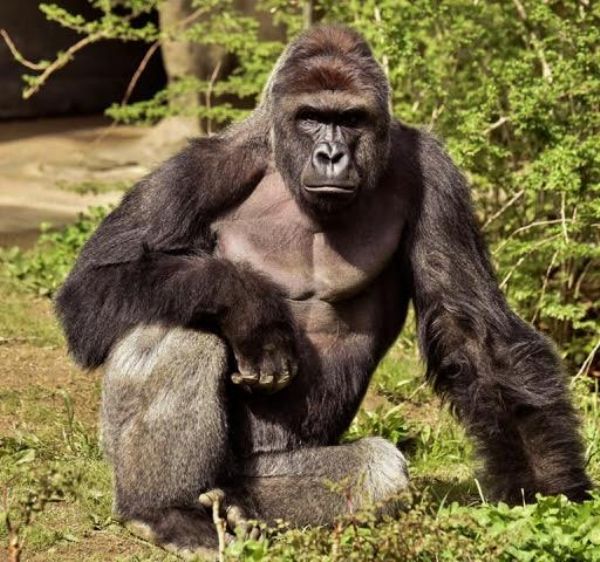

Harambe’s legacy lives on in America’s zoos

By Kara Arundel By Kara Arundel

May 22, 2017

When Harambe, the gorilla, was shot and killed a year ago Sunday at the Cincinnati Zoo, the outcry was explosive. Some found fault with the zoo staff who shot the gorilla in order to protect a toddler who fell into the gorilla enclosure.

Some blamed the mother for not keeping a closer eye on her child. Many questioned why the gorilla couldn’t have just been tranquilized. Countless others asked why the large, intelligent and critically endangered western lowland gorilla was living in a zoo in the first place.

Harambe is gone, but his legacy lives on, and not just in silly memes. Harambe was one of about 350 gorillas living in zoos in North America. Scattered across those zoos live Harambe’s relatives. While Harambe never had any offspring of his own, he had many aunts, uncles, cousins and an astonishing 12 half-brothers and half-sisters. His genetic line is well-represented in the current population of gorillas living in captivity.

|

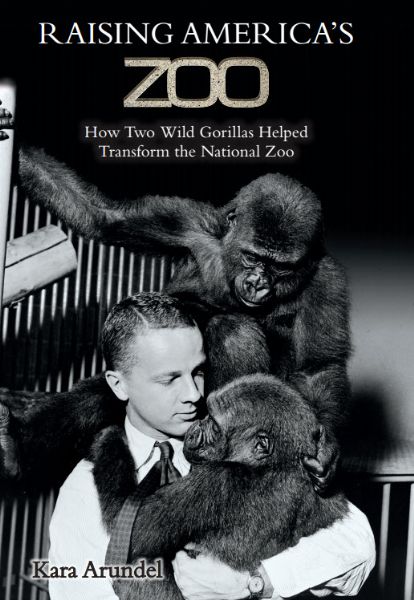

Due out in Summer 2017

About the book:

Raising America’s Zoo shares the heartbreak and triumphs of these first-generation zoo gorillas and their caregivers who worked tirelessly to make their lives better. Witness the personal story of Nick Arundel, a man who at first celebrated their capture, then grew to regret his tale of hunting gorillas, and spent the rest of his life as an advocate for animal conservation. Experience the National Zoo’s voyage of contentious responsibility, limited capacity, joyful discoveries, and urgent deadlines to preserve western lowland gorillas. As gorillas move closer to becoming extinct in the wild due to habitat destruction, disease, and poaching, the zoo community’s mission to save gorillas may be more important now than ever before.

“Timely, heart-wrenching, and triumphant, Raising America’s Zoo is a compelling read for anyone interested in animal conservation. What Nick

Arundel did to preserve the environment and animals will withstand many generations.”

—Former Rep. Paul “Pete” McCloskey, Jr., co-author of the 1973 Endangered Species Act and co-chair of the original Earth Day

About Kara Arundel

Kara Arundel has worked as a journalist for two decades in Florida, Virginia, and Washington, D.C. To research this book about the National Zoo and her father-in-law, she reviewed thousands of pages of documents at the Smithsonian Institution Archives and conducted more than two dozen interviews with those most familiar with the zoo and gorillas. She lives in

Washington, D.C., with her husband and two sons.

To reserve a copy of the book, subscribe to this News Hub and you'll be alerted when the book is ready.

|

And without Harambe’s many relatives and other captive gorillas, the world would be closer to having no gorillas exist at all.

See, gorillas come from only one place on Earth – Equatorial Africa. All four sub-species of gorillas are critically endangered, according to the Red List of Threatened Species from the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. The wild gorillas are one step away from being declared extinct. The western lowland gorilla’s population in the wild could plummet by 80 percent by 2071, because of habitat destruction, poaching, disease and climate change, according to IUCN.

Harambe’s parents were born in American zoos, but all four of his grandparents came from the wild. “African” is the only description of the location of their births in the 1960s as recorded in the Western Lowland Gorilla North American Regional Studbook.

Hunters captured these first-generation zoo gorillas through violent methods, including tracking and killing the parents in order to catch the young apes. Very young baby gorillas taken from their mothers needed to be hand-fed infant formula out of baby bottles in order to survive.

It wasn’t until the 1970s when national and international restrictions put a stop to the hunting, exportation and importation of gorillas. The zoos’ supply of wild gorillas was cut off and those institutions had to figure out how to successfully breed and sustain their own populations of gorillas.

If a zoo got lucky, their mature male and female gorillas did what comes naturally and their offspring would be born nine months later. But joyous zoo owners and keepers were jittery about leaving a newborn with the parents, considering the efforts it made to get the parents from Africa. It became a common practice – at least in some American zoos – to remove the newborn gorilla from its mother and have the wife of a zoo keeper or director raise the baby for its first few months.

These young gorillas were doted on and treated like members of the family. They ate in high chairs and slept in cribs. They even made outings to the grocery store or other places about town dressed in baby clothes.

But this reliable and predictable gorilla rearing protocol had problems. Some hand-raised gorillas struggled to find mates and breed once they returned to the zoo and reached maturity. Their difficulties, it was later discovered, was partly caused by human-raised gorillas not getting essential gorilla socialization skills early in life. Zoos in America realized there would be no way to sustain the captive population of gorillas and keep a healthy level of genetic diversity among the apes.

Zoos that housed gorillas shed their competitiveness with each other and started cooperating in order to match unrelated gorillas with possible mates. They created a Gorilla Species Survival Plan and evaluated what each gorilla in captivity could contribute to the overall population. Zoos built more natural indoor and outdoor enclosures to accommodate new gorilla family dynamics. They let newborn gorillas stay with their mothers. They gave the captive gorillas more respect.

Now, only 50 years after hunters violently captured young gorillas from Africa to bring to American zoos, accredited zoos say they can maintain 99 percent genetic diversity in the captive gorilla population for at least 100 years and 90 percent genetic diversity for 400 years, according to the gorilla survival plan.

One day in the future, captive gorillas may be the only gorillas left on Earth.

Harambe and his family play a big role in protecting the next generations of captive gorillas. That’s Harambe’s lasting legacy.

Kara Arundel is a Washington, D.C.-based reporter and author of Raising America’s Zoo, to be released this summer. She can be reached at 202-276-5494 or by email at karacarundel@gmail.com

|