Records lawsuit docs: Brock’s Audit Department structure violates government auditing standards

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||

| Description | ||||||||

|

Records lawsuit docs: Brock’s Audit Department structure violates government auditing standards Two hats equal conflict: Brock’s Finance director signs off on hundreds of millions in payments, also serves as Internal Audit chief April 24, 2014 By Gina Edwards Naples City Desk

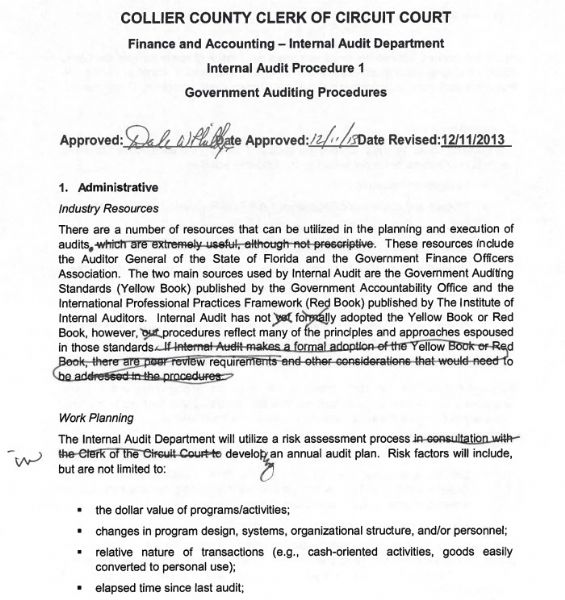

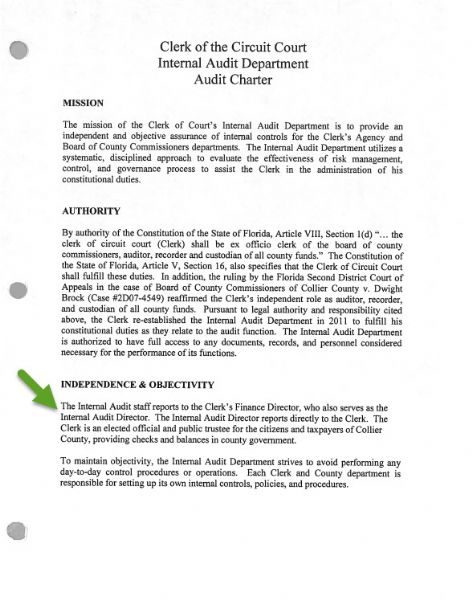

Collier Clerk of Courts Dwight Brock, who serves as the county’s independently elected auditor and custodian of all county money, has structured his Internal Audit Department in a way that violates widely accepted professional standards for government and internal auditors. The Internal Audit Department structure is outlined in the policy and procedures manual obtained by Naples City Desk in a public records lawsuit against Brock.

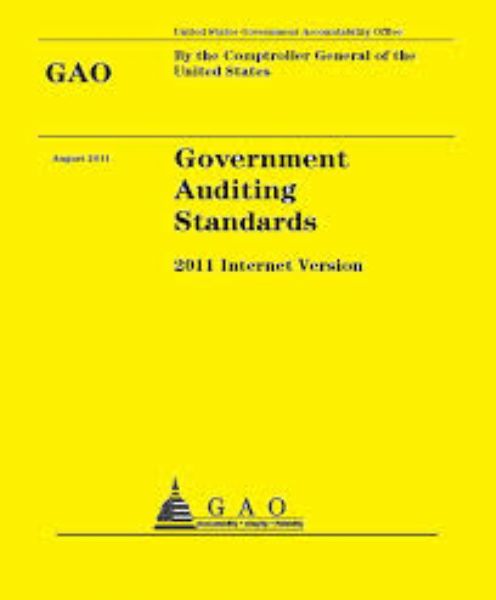

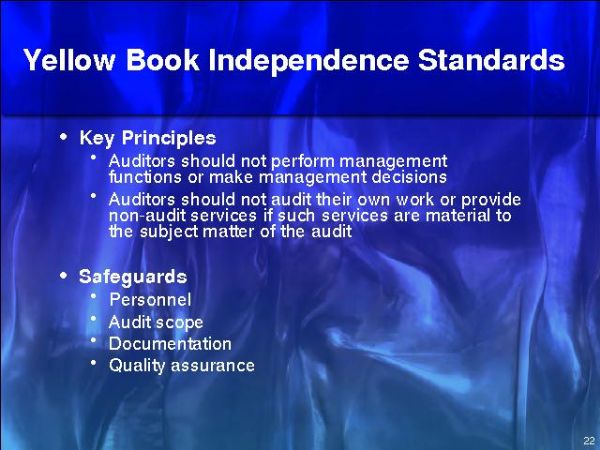

Brock’s Finance Director, Crystal Kinzel, who has broad responsibility for preparing Collier County’s financial statements, signing off on hundreds of millions of dollars in county government payments, and tracking custody of the county’s financial assets — is also designated as Brock’s Internal Audit Director. Wearing these two hats at the same time creates an inherent conflict of interest for Kinzel and it’s a practice that is specifically prohibited in the Government Auditing Standards manual, known in the industry vernacular as “The Yellow Book.” The structure is also specifically prohibited in practices outlined by the leading industry group, the Institute of Internal Auditors. In simplest terms — an auditor can’t audit himself or herself. The standards say that making payments, authorizing transactions, and having custody of assets fundamentally impairs the independence of an auditor because an auditor can’t objectively review their own conduct.

Approving transactions and having custody of the county’s assets is Kinzel’s role as Finance director. Dr. Terry Engle, a professor who teaches auditing at the University of South Florida in Tampa, says an employee serving as Finance director over day-to-day operations and also over Internal Audit is a violation of industry standards. “This is bad,” says Engle. “This is not appropriate. You’re not independent. It’s almost a charade.” Brock, as an independently elected auditor, answers to the voters and he isn’t necessarily required to follow industry auditing standards. But how Brock, a CPA and an attorney, operates his office is not the norm for other elected clerks. In Lee County, for example, the Internal Audit director reports directly to the elected Clerk and has no responsibilities or involvement in day-to-day financial and accounting matters like the Finance director does. Pasco County Clerk Paula O’Neil, president of the statewide Florida Court Clerks and Comptrollers Association, describes the importance of the separation on her web site: “The Director of Internal Audit reports directly to the Clerk & Comptroller, an elected official, thereby maintaining independence from activities audited. Objectivity is essential to the audit function. Therefore, the Internal Auditor should not develop or install procedures that will be later reviewed.” At the state level, the head of the Division of Accounting & Auditing for Florida state government at the Department of Financial Services, Christina Smith, says a local Finance director involved in day-to-day operations should not be serving simultaneously as Internal Audit director.

“It’s a conflict of interest,” Smith says. “It’s understood in the industry. If you have someone operating your controls you shouldn’t also have that person evaluating them.” Internal controls — policies to prevent fraud — are the buzz in Tallahassee right now, says Smith. A bill making its way through the legislature, S.B. 1628, would require local governments, school districts and other government entities to establish, maintain, and document the effective operation of internal controls, including controls designed to prevent and detect fraud, waste, and abuse of taxpayer money and provide the report to the state’s Auditor General. Smith gave this example of an internal control and why it might be needed: A government might create a policy control so an employee who has the ability to create a new vendor account in a financial software system doesn’t also have the ability to authorize a payment on the system to the vendor. Here’s why: A rogue employee could set up a fake business vendor that he or she owns, and then embezzle money by signing off on payments to the fake vendor. External auditors review local government financial statements and those comprehensive annual financial statements are submitted to Florida’s Auditor General each year. But the reports required in the bill making its way through the legislature require local governments to explicitly explain their controls to prevent fraud. “I think policy makers realize how important this is,” Smith says, of having effective internal control. “The clerks are specifically mentioned in there.” Brock declined interview requests and declined to answer questions in writing from Naples City Desk after Naples City Desk was provided access to internal work papers of his audit department beginning on Jan. 22 related to his audit of the affordable housing charity founded by his 2012 political opponent, John Barlow, that received federal and state grant money in 2008. Kinzel has also declined to answer written questions about her work.

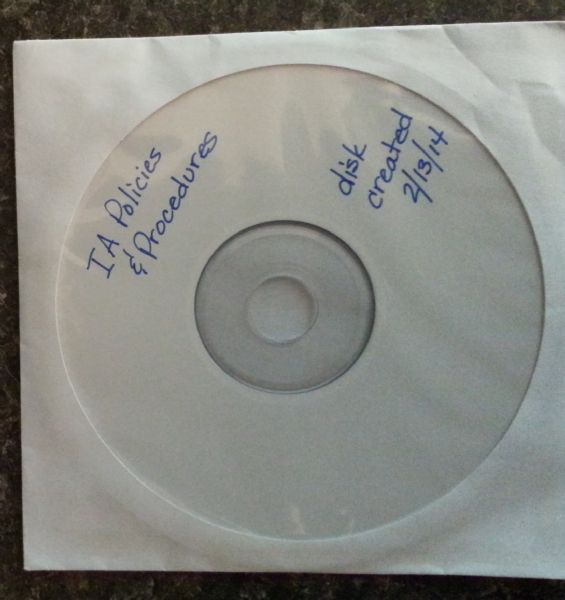

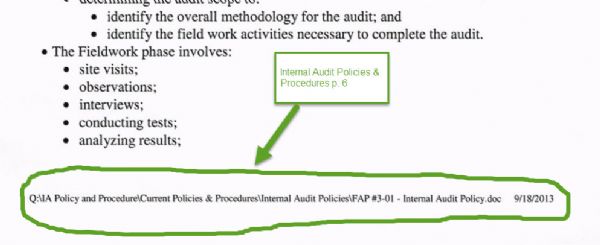

Brock did not respond to written questions from Naples City Desk about his Internal Audit department submitted on Feb. 7, including a question about whether Kinzel is the Internal Audit director. Naples City Desk made a public records request for a scanned copy of Brock’s audit policies and procedures manual. After Naples City Desk published critical stories on Feb. 11 about misleading audit findings Brock publicly made against Barlow, Brock charged this journalist $556 in fees for electronic public records, including $206 for a copy of his audit policy and procedures manual. Naples City Desk, in a letter, urged Brock to release the policies and procedures for free and publish them on the Internet. Subsequently, Naples City Desk filed a public records lawsuit challenging the fees, arguing that Brock can only charge the actual cost of duplication for the electronic records. Brock says he is not subject to the public records law fees and a separate statute governing court clerks allows him to charge up to $1 per page for any document in his possession, not just court records. Collier Circuit Judge Fred Hardt ruled on March 26 that the fees owed are $2 for the electronic public records, not $556. Hardt found that the statute requires clerks to charge fees in keeping with the public records law for electronic records stored in a database. Brock challenged Judge Hardt’s ruling on April 7 and requested a trial. In seeking a trial, Brock asserts that scanned copies of the requested documents did not exist until this reporter made her public records request and once created, the scanned copies did not exist in the Clerk's computer database. Brock argues in court papers that it is Naples City Desk’s burden to prove at a trial that a scanned copy is an electronic record stored in database. In addition, Brock asserts in court filings that the audit policies and procedures “only existed in hard paper form and not in any electronic format at the time that Edwards made her request. Those documents consisted of 206 pages of hard paper copies in a binder. As requested by Edwards they, along with an additional 36 pages of hard paper documents, were scanned into an electronic format and then copied to a CD.” Included on some of the 206 pages are notations including what appear to be computer drive locations and file names like “Q:\IA Policy and Procedure\Current Policies & Procedures\Internal Audit Policies\FAP #3-01 – Internal Audit Policy .doc 9/18/2013” Hardt granted the request and a trial is scheduled for May 27.

Audit or Political Take Down Professional standards call on auditors to perform their work with detached and clinical objectivity: “Public confidence in government is maintained and strengthened by auditors performing their professional responsibilities with integrity. Integrity includes auditors conducting their work with an attitude that is objective, fact-based, nonpartisan, and non-ideological with regard to audited entities and users of the auditors’ reports,” instructs the industry standard Yellow Book. Auditing a political opponent is roundly criticized as a violation of professional standards, academics and industry groups say. Brock is drawing fire following his public allegations that his 2012 political opponent, John Barlow, and the charity he founded called H.O.M.E. potentially engaged in criminal conduct. Barlow and his attorneys have said Brock has abused his office as the county’s elected auditor to exact political payback and publicly trump up false and malicious allegations against H.O.M.E. and its volunteer board members in connection with a $427,000 federal affordable housing grant the charity received in 2008. Barlow and his attorneys say Brock re-opened a closed audit years after the fact in 2013 to smear H.O.M.E. volunteer board members with career and business-damaging public statements including that Brock planned to ask law enforcement to investigate them. H.O.M.E’s volunteer board included Commissioner Georgia Hiller’s 2010 political opponent, Gina Downs, and Russell Budd and Julie Schmelzle, both of whom are high-profile and politically influential business leaders in the Greater Naples Area Chamber of Commerce. Also on the volunteer board was Mel Engel, president of the large commercial builder Boran Craig Barber & Engel. Barlow’s attorney, Jeff Fridkin, said harassment of H.O.M.E. by Brock’s office began shortly after Downs ran against Hiller in 2010. Brock said in an interview that he is not engaging in witch hunts and that anyone receiving taxpayer money should expect significant scrutiny from his office. A Naples City Desk analysis of hundreds of pages of internal audit work papers, deeds mortgages and building permits found that Brock made misleading public statements in January about H.O.M.E. and omitted favorable information, including that H.O.M.E. turned over $427,000 in notes to Collier County, equal to the full amount it received in federal money, after the non-profit closed down in 2010. Brock said more than $400,000 in construction bills submitted by Boran Craig Barber & Engel to H.O.M.E. in connection with remodeling work weren’t backed up with proof that the work was actually done. But a Naples City Desk investigation of Brock’s internal audit files shows that dozens of photos in home appraisal reports — reviewed by Brock’s own staff more than two years ago — and notes from the appraiser document significant remodeling work done. Brock misled the public and Collier County Commissioners when he stated that he stayed out of the process and hired an independent auditor to audit H.O.M.E. to avoid the appearance of impropriety of auditing a past political opponent. Documents obtained by Naples City Desk show Brock himself reviewed at least two draft reports, and that Brock’s Finance Director Kinzel directed the work of Clifton Larson Allen, the firm hired as a consultant, not an auditor, according to its engagement letter with Brock’s office. Auditors are held to higher standards of independence. Barlow’s attorney, Fridkin, says Brock repeatedly called the Clifton Larson Allen report an audit in public to give credence to his false allegations.

Deep involvement, two hats Work papers show Kinzel — as Internal Audit Director — played the lead role in directing the work of consultant Clifton Larson Allen. And 350 pages of documents turned over to Naples City Desk in a public records lawsuit include 6 drafts that went back and forth between Kinzel and the consultant and a personal review by Brock, contradicting his public statements that he stayed out of the process. (See related story) Meeting memos and emails show Kinzel ordered Clifton Larson Allen to add houses that received no federal grant dollars which skewed grant profit calculations against H.O.M.E. H.O.M.E. received $427,000 in federal grant money and used all of it to buy 7 houses. Kinzel misrepresented to the consultant, meeting memos show, that H.O.M.E. used profits from federal funds to buy 6 houses. In fact, H.O.M.E. used all private money — personally financed by Barlow — to buy 6 houses. Publicly filed deeds show every house that was part of the federal grant program was purchased by H.O.M.E. before the first house was sold to a low-income buyer. That makes Kinzel’s profit assertions false on their face. Kinzel’s false misrepresentations are significant. They formed the basis for Brock to justify a continued audit by his office under the guise that H.O.M.E. owed program profits back to Collier County. Federal grant guidelines give credit for private contributions as part of calculations of program profits. A county budget analyst, in a rebuttal to Kinzel and Internal Audit in 2011, found that H.O.M.E. didn’t owe program profits back to Collier County based on the fact that less than a third of H.O.M.E.’s project was funded with federal money. A county housing department employee had reached the same conclusion the year before when H.O.M.E. closed. In addition, Kinzel also told Clifton Larson Allen that there was little documentation to back-up construction remodeling work, memos show. An internal auditor working for Kinzel in 2011 and 2012 reviewed appraisal reports with photographs and notes documenting extensive remodeling work done on the houses. The internal auditor, Allison Kearns, documented her review of the appraisals in a note in her audit work paper files. Kearns, who no longer works for Brock’s office, didn’t question the construction remodeling work in her report of February 2012 that closed without major findings against H.O.M.E. Kinzel — as Finance Director — provided input on H.O.M.E.’s grant contract in 2008, and alerted the county that she believed a broader contract with H.O.M.E. involving state money should be in place, as opposed to the county’s routine procedure in which the county loaned low-income homeowners the money for remodeling work and then paid contractors directly. Making sure proper controls are in place is part of Kinzel’s job. The county attorney’s office agreed with Kinzel. Kinzel’s stance drew criticism from Barlow, and correspondence files in the audit work papers show heated exchanges between Kinzel and Barlow. In 2008, Barlow had met with Kinzel and Brock months before launching his charity affordable housing project to get input and advice to make sure payments would flow smoothly. Later, Barlow complained to Kinzel that state grant money for remodeling contractor payments had been held up. H.O.M.E. received $50,000 in state grants to remodel its first “test house.” Later, H.O.M.E. was awarded $150,000 in state money to put toward remodeling other houses in the program, but that money didn’t actually flow to H.O.M.E. That money went to Collier County and county housing department officials paid contractors directly and Kinzel’s Finance staff signed off on the validity of the payments. Kinzel personally worked with her Finance Department staff to sign off on payments to H.O.M.E. for the original purchases of the 7 houses with federal grant money, internal documents show. Later, she urged county staff to pull a Jan. 11, 2011 item off county commissioner’s agenda to officially accept $427,000 in notes from H.O.M.E., documents show. H.O.M.E. gave $427,000 in down payment assistance to low-income buyers in the form of zero-interest loans that have to be paid back in 30 years or whenever the houses resell, whichever is sooner. Providing the down-payment assistance to low-income buyers was H.O.M.E.’s plan to use its “program income” or profits from selling the houses, and it’s expressly allowed under federal grant rules. And Collier County Housing staff approved the down-payment assistance plan in 2009, as required by H.O.M.E.’s contract with Collier County. The notes are an asset: The $427,000 will be paid back to Collier County in 30 years or whenever the houses in the H.O.M.E. program resell to new buyers, whichever comes first. Distressed that the official County Commission vote had been held up, H.O.M.E.’s real estate attorney filed legal documents in the official records to assign the notes to Collier County in March 2011. Brock, in his January public presentation, accused H.O.M.E. of violating its county contract by providing the down payment assistance to low-income buyers. The consultant, Clifton Larson Allen, wouldn’t side with Brock on that claim in the firm’s report, internal documents show. Brock failed to tell commissioners — and the public — that H.O.M.E. had paid back the county the $427,000 in notes. Instead he said H.O.M.E. still owes the county $75,000.

Fear of losing your job Whether Kinzel made critical mistakes or whether her actions were justified is something an Internal Auditor would typically evaluate. But under the set-up in Brock’s office, internal audit staff are placed in the position of evaluating the day-to-day Finance Department actions of their boss — Kinzel, who is wearing the Internal Audit Director hat as well. And Kinzel can’t audit herself. The set-up puts Brock’s Internal Audit Department staff in a tenuous situation, according to Stephen Goodson, an audit director in Texas state government who sits on the national Education and Research Committee for the Institute of Internal Auditors. “As internal auditors we need to be frank about our conclusions and findings without fear of losing our jobs,” Goodson said. “You can’t report on if your boss did something wrong… We can’t be fearful of losing our jobs.” As Internal Audit Director, Kinzel also has the ability to influence what audits get done, creating the potential to steer scrutiny away from certain Finance Department operations she oversees. Typically, an Internal Audit Director would report directly to the elected official. In Lee County, Internal Audit Director Tim Parks reports directly to Clerk Linda Doggett. Parks says the set-up protects the integrity of the audit function. His department is in the process of upgrading to create an inspector general-type office geared to fraud detection. The office is also in the process of officially adopting Institute of Internal Auditor standards in the “Red Book” that call for a peer review of audit operations, a formal process that Park says can take 18 months. “By having these standards it attempts to take the politics out to the extent possible,” Parks says.

At a court hearing in March in the public records lawsuit, Brock agreed to turn over his Audit Department’s policy and procedures to Naples City Desk and stay fees while the court determines what fees are owed. The audit policy documents show that Dale Phillips, an Internal Audit Manager under Kinzel, proposed new procedures to upgrade standards. In a handwritten strike-through, someone crossed out a provision that the Internal Audit Department will develop an annual audit plan “in consultation with the Clerk of the Circuit Court.” A reference to audit evaluations by a proposed Clerk’s audit committee was also crossed out. Included in Phillips’ proposals was a statement that the department will use the Yellow Book and Red Book standards. But an indication that Brock’s Internal Audit Department may formally adopt the standards and undergo peer review in the future was crossed out in a handwritten edit. Kinzel’s role as Internal Audit director and Finance director wouldn’t hold up to peer scrutiny based on industry standards. It’s unclear whether Kinzel, Brock or someone else crossed out the proposal for the peer review in the handwritten notes. Brock’s office didn’t respond to a question by Naples City Desk about the handwriting. |

| Other Images | |||||||||

|

| Paid Story |

| You don't have permission to view. Please pay for this story to gain access. |

| Paid Video |

| Ask a question or post a comment about this story | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Subsequently, Naples City Desk filed a public records lawsuit challenging the fees, arguing that the requested documents aren't court records and Brock can only charge the actual cost of duplication for the electronic records, or the cost of the CDs.

Subsequently, Naples City Desk filed a public records lawsuit challenging the fees, arguing that the requested documents aren't court records and Brock can only charge the actual cost of duplication for the electronic records, or the cost of the CDs.

Included on some of the 206 pages are notations including what appear to be computer drive locations and file names like this one on page 6 “Q:\IA Policy and Procedure\Current Policies & Procedures\Internal Audit Policies\FAP #3-01 – Internal Audit Policy .doc 9/18/2013”.

Included on some of the 206 pages are notations including what appear to be computer drive locations and file names like this one on page 6 “Q:\IA Policy and Procedure\Current Policies & Procedures\Internal Audit Policies\FAP #3-01 – Internal Audit Policy .doc 9/18/2013”.